Opinion

Football clubs are not built overnight. They are shaped slowly, by players, coaches, supporters, and moments that linger long after the final whistle. In Zwolle, that story stretches back 115 years.

Founded on June 12, 1910, PEC Zwolle reaches a landmark anniversary this season, and the club is marking the occasion in fitting style. Zwolle Originals is more than a kit launch; it is a celebration of identity, continuity, and the figures who helped shape both the club and the city.

Shot with a selection of true club originals — including Jaap Stam, Tijjani Reijnders, and Arne Slot — the campaign bridges generations, bringing together eras that define Zwolle’s footballing DNA.

At its heart, Zwolle Originals is about recognition. Recognition of the players and coaches who left a lasting imprint and whose influence is still felt today. From Bram van Polen to Co Adriaanse, from Henk Timmer to Albert van der Haar, the campaign gathers together names that resonate deeply with supporters.

The anniversary celebrations culminate in Zwolle Originals Matchday on Saturday, January 31st — a moment dedicated to reflecting on the club’s rich history and the people who helped build it. These are the figures many supporters grew up watching, learning from, and celebrating; individuals who turned Zwolle from a name on a fixture list into a shared emotional reference point.

To mark the milestone, the club is also releasing a limited-edition Zwolle Originals 115th anniversary shirt. Featuring all of the aforementioned icons, the shirt serves as both a wearable tribute and a piece of living history.

In an era often obsessed with the next signing or the next season, Zwolle Originals pauses to look backwards, not out of nostalgia, but out of respect. It is a reminder that clubs endure because of their people, their stories, and their ability to honour where they come from.

Latest

All words and images by Guirec Munier

“A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.”

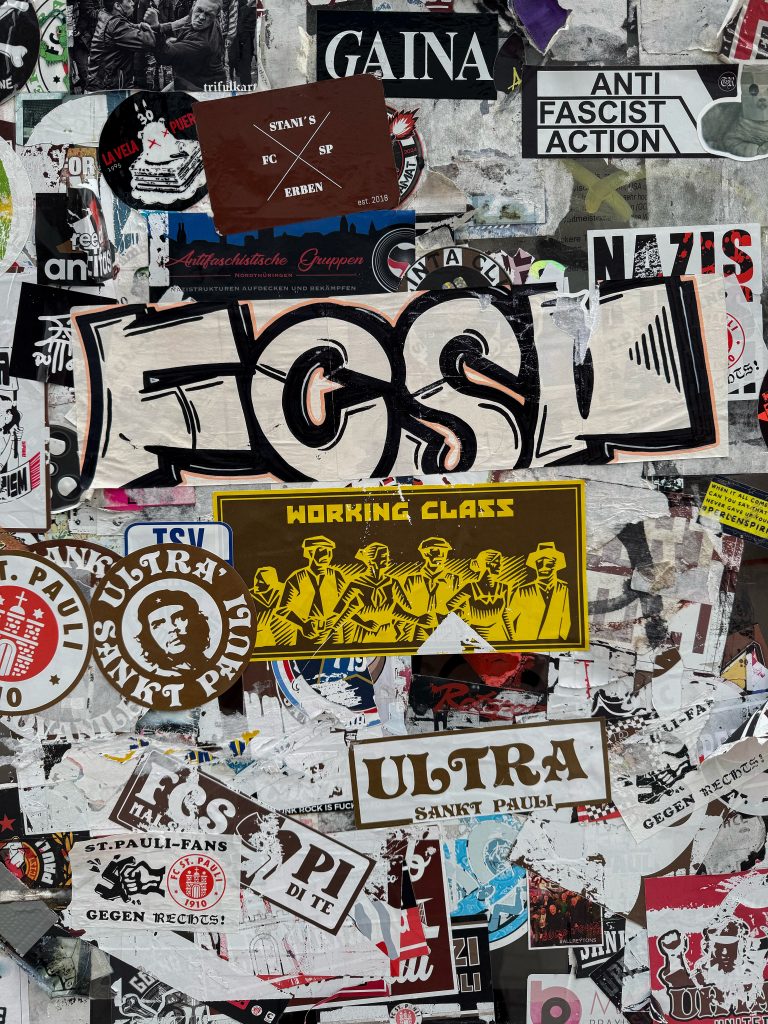

Inside the World of FC St. Pauli

Sankt Pauli. The mere mention of the name evokes a world of its own, stirring strong and often opposing emotions. FC St. Pauli is a neighbourhood club — but not just any neighbourhood. It belongs to the alternative district of Hamburg, Germany’s second-largest city and Europe’s third-busiest port.

This is a district bisected by the Reeperbahn and its surrounding streets, where strip clubs, sex shops, and brothels form the heart of Hamburg’s red-light district. A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.

That spirit would come to define FC St. Pauli itself.

Founded in 1910, the Braun und Weiß club underwent a dramatic transformation in the mid-1980s. Until then largely apolitical, the club took a sharp turn as squatters, punks, and other outsiders found refuge on the right bank of the Elbe. These marginalised groups soon formed the core of the fan base, particularly throughout the 1990s, standing as an island of resistance in a German football landscape plagued by neo-Nazi hooliganism.

Championing anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-sexist values — alongside vocal support for refugees and LGBT+ rights — FC St. Pauli became an emblem of the left. A football club like no other.

Whatever one might think, football is undeniably political. And what better symbol to represent resistance than a pirate flag? Thus, the Jolly Roger was adopted at the initiative of supporters. Few could have imagined at the time that this gesture would become such a powerful and profitable symbol. So much so that FC St. Pauli supporters are now the only fans in Germany who often don’t wear their club’s official colours.

This fusion of alternative culture and sharp branding has allowed the club to grow far beyond Hamburg and German borders. Today, FC St. Pauli is among the four German clubs generating the highest revenue from merchandise sales, alongside Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund, and Schalke 04.

This commercial success appears to contradict the club’s values — yet how else can they compete without the financial rewards enjoyed by Europe’s elite? Especially when they remain the only fan-owned club playing in one of the top five European leagues.

In a further expression of this model, the club recently sold the Millerntor-Stadion in the form of shares to more than 21,000 supporters. The stadium is now leased back to the club by its fans.

Before every home match, die-hard supporters gather in a convivial space beneath the Gegengerade — the stand holding more than 10,000 standing spectators. Here, alternative subcultures, anarchists, and activists of all kinds mix freely. In the Südtribüne, each game becomes an opportunity to raise awareness or promote a humanitarian cause. At the Millerntor, there is no expectation that you leave your brain at the turnstiles.

Yet divisions have emerged in recent times. Since the war in Gaza, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict has exposed deep fractures within the European left. In Germany, a traditionally pro-Israel stance — shaped by historical guilt linked to Nazism and the Holocaust — increasingly clashes with positions held by left-wing movements elsewhere in Europe, many of which express stronger support for the Palestinian cause.

These tensions are visible within the FC St. Pauli community itself, particularly between local supporters and international fan clubs. Several overseas fan groups have voted to dissolve, and the historic friendship between Ultra’ St. Pauli and the Green Brigade did not survive the fallout.

The German left remains trapped in a German-centric reading of Israeli policy — a stance that continues to divide.

Gegen Rechts. Everywhere.

All words and images by Guirec Munier

Words and images: Markus Blumenfeld

We spoke to filmmaker, storyteller and creator of The Global Game, Markus Blumenfeld, about football and culture in Japan, a country where the sport has been carefully shaped, curated, and woven into everyday life.

From the J.League’s ambitious “hundred-year vision” to rooftop pitches in Tokyo, family-filled terraces in Nagasaki, and train journeys linking cities rarely mentioned in the same breath, Markus reflects on a football culture defined not by chaos or confrontation, but by discipline, balance, and quiet intensity.

His journey traces how the game lives beyond matchday, through fashion, food, design, and shared public spaces—and how Japan has built a football identity that feels uniquely its own.

A Long-Standing Curiosity

Japan had been sitting in the back of my mind for years—a place people describe with the same words they use for good football: precise, disciplined, and beautiful when it all comes together. What finally pushed me to go was hearing about the J.League’s “hundred-year vision,” the idea that a country could try to engineer its football future as carefully as it builds skyscrapers or subway networks. I wanted to see it firsthand.

Following the Game by Rail

I based myself in Tokyo and moved mostly by train, tracing the game through cities that don’t usually share a sentence: Osaka, Nagasaki, Kashiwa, Iwata, and Tokyo. Along the way, I encountered a football culture that feels singular.

In Japan, football isn’t confined to matchdays; it’s woven into fashion, transit, food, and design. The J.League didn’t simply import the sport; it curated it, selecting the most expressive and beautiful elements from football cultures around the world and shaping something distinctly its own.

Football in the Everyday

In Japan, the game lives everywhere—maybe not as overtly as in the favelas of Brazil or the beaches of Morocco—but on rooftops in Shibuya, in pickup sessions in parks, and on the racks at 4BFC, where vintage J.League shirts hang beside copies of SHUKYU, a Japanese football culture magazine and design studio.

I spent days with my friend Kai just walking and playing, juggling in alleys, trading passes on tiny concrete courts hidden behind apartment blocks, riding trains out toward Mount Fuji to find a pitch with the mountain sitting perfectly behind the goal.

Nagasaki and the Power of Belief

Further south, I stood pitchside watching V-Varen Nagasaki fight for promotion to J1. These fans weren’t the usual suspects I’ve seen in my travels, hooligans with buzzcuts and tattoos, but instead families, elderly women, and children standing shoulder to shoulder, chanting in perfect unison for six hours straight.

A promotion race in the second division had pulled an entire port city into the same rhythm.

Development, Disappointment, and Perspective

In Osaka, at Cerezo’s training ground, academy coaches talked about developing players who can leave for Europe and not get lost—footballers equipped not just technically, but culturally and mentally.

Back near Tokyo, I watched Kashiwa Reysol win their final match of the season, only to miss out on the title by a single point. The margin was brutal, but the response wasn’t. The following day, the team’s captain, Tomoya Inukai, invited me to meet him at his café, sit with his family, and talk about his belief that life is about so much more than football—and the many things he does to live a balanced life.

It’s the kind of invitation that simply wouldn’t happen in most other places.

A Different Kind of Intensity

Compared to Brazil or Serbia, Japanese football feels less explosive on the surface, but it runs just as deep. The stands are loud, the tifos huge, yet the atmosphere is strangely gentle—kids and grandparents in the ultras section, orderly queues for yakitori, everyone cleaning up their own mess.

None of this compromises the energy. They don’t need hate to fuel their rivalries, only passion and pride for their club.

Come Hungry

The Japanese brand of football is special, and if you’re lucky enough to visit this beautiful country, come hungry.

Eat what’s sizzling outside the stadium—yakitori, karaage, regional specialities you can’t pronounce yet. Ride trains to places that aren’t in the guidebooks. Get lost in side streets and izakayas. Go to a J.League match. Join the crowd and relish the songs and the atmosphere.

Have a freshly poured Japanese beer. Have another. Make friends in the stands and experience a culture and passion for football unlike anywhere else in the world.

Words and images: Markus Blumenfeld

Markus Blumenfeld is the creator of The Global Game, a docu-series that captures the stories, fans, and moments that make football special. Using the beautiful game as a lens to view the world, the series explores football as an unspoken language—one that connects people from different places, backgrounds, and cultures. A uniting force in a divided world.

You can also find The Global Game on YouTube

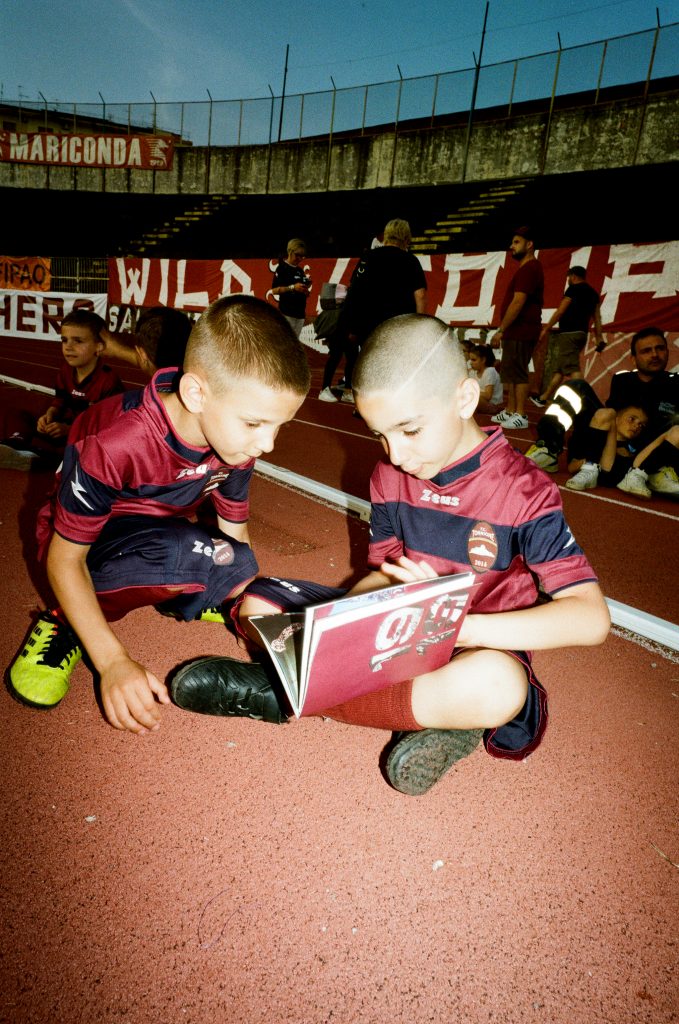

All images by Alessandra Francesca Coppola

“Fighting and believing in a dream driven by the faith in a team that represents the pride of a city and its people.”

There is no gentle way to explain why Salernitana are in Serie C. Relegation rarely arrives with poetry attached. It arrives with balance sheets, tribunal rulings, and fixture lists that suddenly look unfamiliar. By the summer of 2025, the club had slipped out of Serie B following the relegation play-off, completing a sharp fall from Serie A just a season earlier.

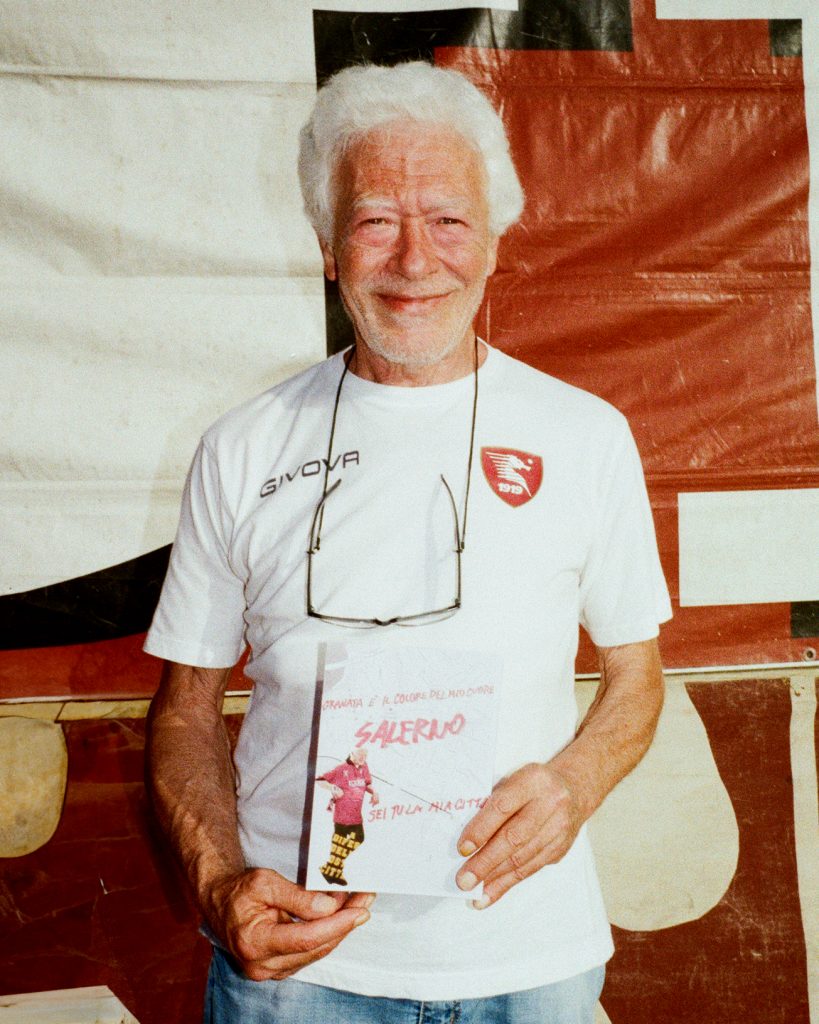

For Alessandra Francesca Coppola, a photographer who has spent years documenting the club and its supporters, league position is only part of the story.

“Salernitana represents that ‘old-school football’ that is slowly disappearing,” she says. “A club from southern Italy that doesn’t benefit from the same privileges as others, especially the big teams.”

That sense of imbalance has always hung over Salernitana. Founded in 1919, the club has been liquidated, refounded, renamed, and rebuilt multiple times across its history. Stability has come in short spells, usually followed by administrative trouble or relegation. This is not nostalgia; it’s an institutional fact. Salernitana have spent far more of their existence navigating the lower divisions than enjoying the top flight.

When they did return to Serie A in 2021 after a 23-year absence, it came with caveats. Ownership complications linked to Lazio meant the club was forced into a hurried sale before the season even began. Survival on the pitch was achieved. Stability off it was not. By 2024, Salernitana were back in Serie B. By 2025, Serie C.

Alessandra frames it differently.

“You don’t always win, but you always fight, you never give up.”

That line sounds like a chant, but it functions more like a diagnosis. Salernitana have never been built to dominate Italian football. They have survived it instead, often noisily, sometimes chaotically, and usually without the protections afforded to clubs with larger commercial pull or northern geography.

Their home ground, the Stadio Arechi, reflects that contradiction. Opened in 1990 and owned by the municipality, it holds nearly 38,000 people, far more than most third-tier grounds. On paper, it’s excessive. On matchday, it makes sense.

“The Arechi becomes fire,” Alessandra says. “Chants, whistles, flares, flags that turn the Curva Sud Siberiano into a sea of granata.”

Granata is not just a colour here. It’s shorthand for belonging. Salernitana’s identity has always snapped back to it, regardless of crest redesigns or corporate resets. Players come and go. Owners change. The shirt stays the same.

“The grit and devotion of the Granata supporters are unique and famous throughout Italian football, so much so that even players know about it.”

That reputation travels. Opposing players mention it in interviews. Managers prepare for it. The atmosphere often feels disproportionate to the level of football being played.

“Every match feels like a Champions League final!” Alessandra says — not as exaggeration, but as observation.

And yet, context matters. Salernitana are not an abstract idea of passion; they are rooted in Salerno, a port city on the Tyrrhenian Sea with a long memory and a defensive sense of self. Founded as a Roman colony in 197 BC, Salerno has spent centuries being passed through, ruled over, and landed upon. During the Second World War, it became a frontline again, hosting the Allied landings of Operation Avalanche in 1943.

Football clubs absorb the psychology of their cities. Salernitana have absorbed Salerno’s: wary of outsiders, sceptical of authority, slow to trust, quick to rally.

That’s why Coppola’s words about belief carry weight in a season like this one.

“And yet here we are, in Serie C, fighting and believing in a dream driven by the faith in a team that represents the pride of a city and its people.”

There is no talk here of “sleeping giants” or inevitable returns. Serie C is not treated as a narrative device. It is treated as a place you survive until you don’t have to anymore.

The club’s traditional nickname, Bersagliera, is still sung, still written on banners, still shouted into the cold air on nights when logic suggests staying home.

“Avanti Bersagliera.”

It’s not a rallying cry for glory. It’s closer to a statement of persistence. Keep going. Keep turning up.

In an era where Italian football increasingly mirrors European trends — consolidation, branding, risk management — Salernitana remain awkward to categorise. They are too big to disappear quietly and too unstable to settle comfortably. That tension defines them more than any league table.

Alessandra puts it most plainly when she recalls a chant that cuts through all of it:

“Jamm a vrè, non tifo per gli squadroni ma tifo te” — Let’s be clear, I don’t support the big teams, I support you.

Not success. Not scale. Not the idea of football as a product.

Just the club.

All images by Alessandra Francesca Coppola

All words and images by Guirec Munier

On the Ruins of Hanappi

On this summer Sunday in the Hütteldorf district of western Vienna, the Weststadion stands on the ruins of the Hanappi-Stadion, the former home of Austria’s most popular and successful club, Rapid Wien. While Viennese supporters and those of FC Blau-Weiß Linz share the same Biergarten without any animosity, Rapid Wien ultras gather in front of the entrances to Block West two hours before the Bundesliga season kicks off.

As with virtually every home game, Block West is sold out. Eight thousand people—mostly ultras—coexist and coordinate despite belonging to different groups. Owing to their seniority, the two Ultras Rapid capos set the tone. The first ultra group in the German-speaking world, Ultras Rapid are accompanied by the club’s two other main ultra groups: the Tornados and the Lords. One group initiates the chants, with the other two following from their respective perches in the stand.

Belonging to Block West

But you don’t need to enter the stand to see how deeply the ultras identify with Block West. In the passageways, murals created in honour of the ultra groups cover the concrete walls, while stickers adorn almost every door and surface.

The Rapid-Viertelstunde

As the minutes tick by, Block West roars again and again for its team, igniting numerous flares and unfurling a sea of flags. Then, at the start of the final fifteen minutes, led by Block West, the entire Weststadion rises to its feet and claps passionately for a full minute. This is the Rapid-Viertelstunde.

In the 75th minute of every match, fans honour this century-old tradition—a tribute to the fighting spirit of Rapid Wien, whose teams famously turned countless matches around in the final fifteen minutes during the 1920s. In a stadium in 2025, it is a rare sight: no one reaches for their smartphone to immortalise the moment. Here, they don’t take photos; they sing. Block West deliberately cultivates a touch of darkness.

After the Whistle

At the final whistle, following a match dominated by Rapid Wien, the 8,000 supporters—who had merged into one only moments earlier—gradually dispersed onto Gerhard-Hanappi-Platz.

All words and images by Guirec Munier

All words and Images: Will Dunn

Driven by a long-standing connection to Moroccan football and memories of unforgettable nights in Casablanca, Will Dunn returned to Morocco to document the heart and soul of this year’s Africa Cup of Nations. Having previously experienced the raw intensity of Raja and Wydad matches, the opportunity to witness AFCON on Moroccan soil felt impossible to ignore.

From packed cafés and flag-draped streets to thunderous stadiums alive with colour and noise, his journey became a celebration not just of football, but of the culture, community and shared passion that defines the tournament.

A Return to Morocco

I had the chance to spend a month in Morocco a few years ago and bounded around by train and bus, taking in everything the country had to offer. The memories from that trip that stayed with me the most were the two matches I saw in Casablanca, Raja and Wydad playing over the course of the weekend.

I’d always heard how passionate the fan bases were for the big teams, but the support had to be seen to be believed. I had always wanted to get back out to Morocco, and when I saw that AFCON was out there this time around, I jumped at the opportunity to return.

Football Everywhere

Football is everywhere in Morocco. You only have to walk through the souks and past the cafés to see football matches from across the globe being shown on TVs, or souk vendors watching matches or highlights on their phones.

The cafés are brimming with locals sipping tea, glued to AFCON. Away from the international stage, your attention is caught by murals for local clubs adorning the sides of buildings and the visceral enthusiasm around the return of the Botola League post-AFCON.

Matchday Energy

The support is some of the most impassioned you are likely to see in the grounds. Motorbikes and scooters hurtle towards the stadiums with horns blaring and anticipation building. The sound doubles once you’re inside, with wall-to-wall noise for 90 minutes, with supporters’ groups often arriving an hour before kick-off to build the atmosphere.

In the Stands and Streets

You don’t have to look far before seeing someone walking draped in the flag of a country that is competing or has competed in AFCON. Often, you’ll see people from two countries shaking hands and embracing before games, with mutual respect being the standout feature of fan interaction. Once in the ground, it’s a party-like atmosphere — the noise does not stop.

At half-time, you see those who observe or practise praying in the concourse, a stark contrast to the European football experience, where people bustle to queue up for a pint.

Supporting the Underdog

Standing next to the Senegal supporters for their match against Sudan was a sight and sound to behold. Even the backing for less established footballing nations such as Benin and Burkina Faso had something to offer, not least because the Moroccan support seemed to always back the underdog. Every tackle, pass, cross and rare goal by the smaller teams is cheered furiously.

The memory of Aamir Abdallah scoring his wonder goal for rank outsiders Sudan in their match against Senegal and sending their pocket of supporters wild will live with me forever.

Travelling in the Host Nation

The ease of travel between each city, from Tangier to Rabat and Agadir to Marrakesh, meant moving around such a vast country proved smooth enough. I was very taken by the design of Stade Adrar in Agadir.

In a world where new stadiums often have a copy-and-paste bowl style, it seemed to the untrained eye that those responsible chose to keep true to some semblance of local architecture. For the most part, getting into the grounds, whilst a long way out of town, the queues moved fairly quickly.

On the surface, the apparent conviviality between supporters from different countries has been a real change from a European perspective.

Looking Ahead

I am writing this a few days before the semi-finals and saw both Senegal and Egypt take to the field, who face each other in Tangier. The teams in the semi-finals are those you might expect, with Nigeria and hosts Morocco in the other match.

My gut is saying Morocco, as it’s hard to look past their talent on the pitch, backed by fervent home support. That being said, I would love to see Senegal cause an upset, they were amazing on the pitch and in the stands against Sudan. There is no out-and-out favourite purely on footballing terms in my eyes, and that’s what makes it an exciting finale.

All words and Images: Will Dunn

Ninety Minutes That Last a Lifetime

Words and Images: Joey Corlett

Nothing Comes Close

What can I really say that hasn’t already been said about this fixture? The history, the hatred, the trophies, the relegation of one side — it all speaks for itself. Two colossal footballing institutions, not just in South America but across the world.

All I can say is that whatever lofty expectations you’d rightly have about attending this game, it met them — and then surpassed them with ease. Whatever you’re imagining in your head, add more noise, more colour, more energy, and you may start to come close to what the Superclásico at La Bombonera truly is.

“Add more noise, more colour, more energy.”

Matchday in La Boca

Come matchday in Buenos Aires, I hopped on the bus heading for La Boca. On the streets, I could only spot the Azul y Amarillo of Boca Juniors, and this only intensified with every block passed toward the southern barrio.

We were blessed with beaming sunshine and soaring temperatures, arriving nearly five hours before kick-off. The streets surrounding the stadium were already teeming with delirious fans. Co-opted buses, decked out with Boca banners and flags, rolled in minute by minute, packed with supporters from peñas across the country.

The familiar Argentine terrace soundtrack, trumpets and drums blaring, followed them as they flew by. Some buses even had fans riding on top, waving flags and singing as they surfed along. Here, pasión comes before health and safety.

Through the Streets

Thanks to the guys from Berisso, I grabbed my ticket and was advised to head in early to avoid problems. Cutting through streets filled with the smell of choripán sizzling on the grill and fernet and cola flowing freely, everything felt dialled up to another level. Everyone wore blue and yellow. Every block buzzed with glorious anticipation. Checkpoint after checkpoint passed until, eventually, you found yourself in the shadow of one of the world’s most iconic stadiums.

The Popular Sur

Even entering two hours before kick-off, that feeling was already there. Standing in the lower tier of the Popular Sur, it became immediately clear that you were no longer just an individual fan at a football match; you were part of a swelling, shifting mass of bodies. You had to follow the current, move with the flow. It wasn’t about you anymore; it was about what you could give to the team.

Compared to my experiences in Europe, it was staggering to see how many women and children were present on the terraces for a game of this magnitude, genuinely refreshing to witness. The songs were already in full swing, limbs waving, as the hours flew by toward kick-off.

“It wasn’t about you anymore; it was about what you could give to the team.”

La Doce Had Plans

As the inflatable player tunnels emerged and “Boca mi buen amigo!” swirled around la cancha, La Doce — Boca Juniors’ main barra brava — had plans up their sleeve.

I noticed a few fans with their gaze firmly fixed on the top tier of the stand. After some shouting and pointed fingers, as the players stepped out, I turned to see three enormous tifos unravelling, accompanied by an insane amount of ticker tape that blurred everything in sight.

Before I could even register what the display said, the entire block began pulling down a massive “12” banner, shaking it from side to side while bellowing out songs at full volume. Then, just like that, as the match kicked off, it lifted away — confetti still raining down — and one of the biggest derbies in world football was underway.

“Confetti still raining down — and one of the biggest derbies in world football was underway.”

Chaos and Care

Unfortunately, it took almost until half-time for the first major moment. Exequiel Zeballos danced one-on-one with a River Plate defender before firing home the rebound from his initial shot. What followed was a cascading avalanche of bodies toward the fence in typical Boca fashion.

Amid the chaos, it was incredible to see people diving in to protect children before fully unleashing their celebrations, looking after one another before soaking in the glory of the opener. This sense of collectiveness appeared repeatedly.

There were no stewards in high-vis jackets on patrol, but whenever help was needed, fans stepped in, finding first aid, offering support, or simply checking on each other. Strangers passed around water to beat the heat, hugged whoever was nearby in celebration, and shared in the moment—beautiful organisation and unity within the chaos.

When the TNT Detonates

If the goal before the break lit the fuse, then Miguel Merentiel doubling the lead shortly after the restart was the TNT detonating. Another collective roar erupted as the striker gunned down his defeated opponents in celebration.

At this point, an out-of-form River Plate collapsed as Boca squandered several chances to further salt the wound. As the minutes ticked toward the 90th, the sense of victory grew stronger. In stoppage time, looking down along the terraces, tens of fans dressed in white La B ghost costumes hauled themselves atop the fencing to taunt their crosstown rivals.

Turning around, more flags and banners celebrating River Plate’s relegation suddenly appeared throughout the stadium. Fantastically coordinated shithousing.

Golden Light, Quiet Streets

When the final whistle blew, a shared outpouring of euphoria surged across the ground. Every single person was on their feet — celebrating, climbing for vantage points, crying tears of joy, embracing neighbours, chanting with a unity I don’t think I’ll ever experience again.

I was overwhelmed with emotion, tears welling as the late-day golden light bathed the stadium in an awe-inspiring glow.

It was time to leave, and while I expected the streets to be bouncing, I found the opposite. After nearly five hours of giving every ounce of energy to the team they loved, people quietly took seats in nearby bars or on street corners. Relaxed, beer in hand or paired with grilled meat of choice, each beaming smile spoke volumes about the satisfaction of defeating Las Gallinas.

“I don’t think I’ll ever experience again.”

Boca, Mi Corazón

I feel truly privileged and humbled to have experienced this gargantuan fixture. Even more so to confirm firsthand that it’s every bit as incredible as the stories and history suggest. I’ll tell anyone who’ll listen about this. I’ll tell the grandkids about this. I’ll take these moments to the grave.

Boca, mi corazón.

Words and Images: Joey Corlett