“If a waiter is doing his job correctly, he will be manipulating your perception of reality. He is, to all intents and purposes, an illusionist and his job is to deceive you.” Edward Chisholm.

It’s aggressively cold as I stand in Edinburgh Waverly, looking at the train timetable in abject disgust. A familiar feeling of palpable anger washes over me like a tsunami as I try to come to terms with the cancellation of my train to London. I look around the station and see the same recognisable haunted look in others.

I collect myself and extinguish the fury burning inside. With 3 hours to kill until the next service, I go in search of solitude. I walk to the top of Waverly Station, onto Princess Street, where I’m instantly met with a violent wind that slaps me across the face as if to say, ‘Welcome to Scotland.’

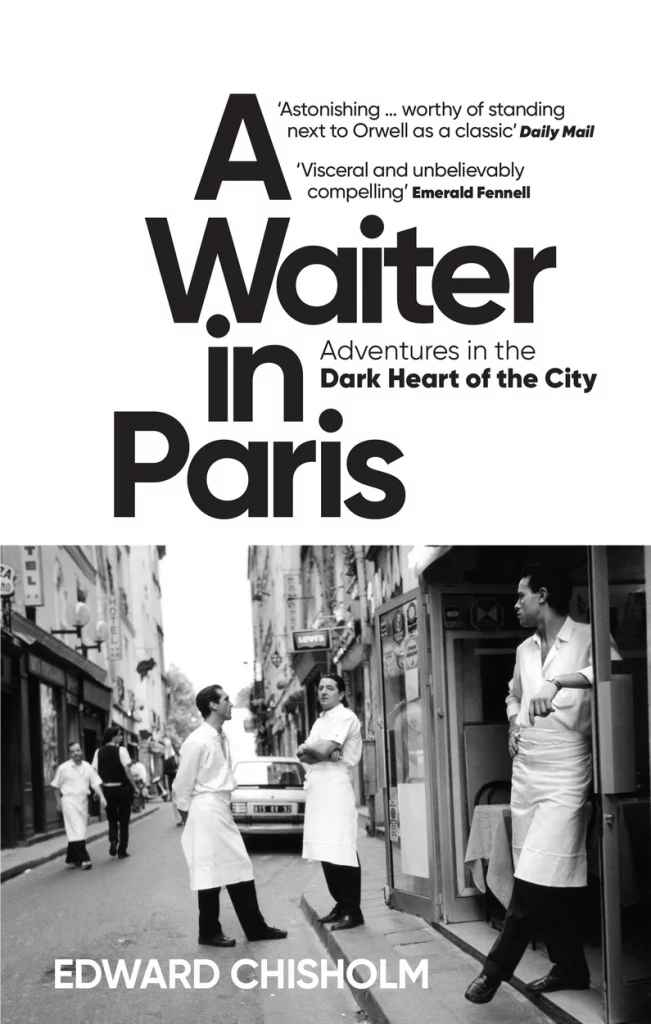

I find shelter in the Golden Hare bookshop and look for a novel to keep me company for the next few hours. It is at that moment, I see it staring directly at me, with its bold font and distinctive black and white cover, ‘A Waiter in Paris: Adventures in the Dark Heart of the City, by Edward Chisholm.

The book is adorned with glowing tributes, comparing it with the works of Orwell and Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential. My morality to never judge a book by its cover is thrown out of the window and directly onto the incredibly damp streets. I buy a copy instantly.

Clutching my book, I make my way to a nearby cafe, order a coffee and begin to read. Now, it has to be said that one of the great joys of reading is that it takes you out of your current circumstances, allowing you to escape into another world. I was no longer in the depths of despair (possibly slightly dramatic) instead, I was now a voyeur into the world of Edward Chisholm, l’Anglais, and his life in the Dark Heart of Paris.

DOWN AND OUT IN PARIS

As the rain lashes down against the window of the cafe, I join Edward he moves to Paris with his French girlfriend Alice. His mind is illuminated with thoughts of grandeur and what a life of being serenaded by the city of love will entail. He is lost in the daydreams of Hemingway, Fitzgerald and George Orwell and thoughts of one day becoming a writer.

‘I’d wanted to live abroad for so long, but with the crap jobs, I was doing in London, I could never get the money together to go abroad.’ Chisholm explains when we catch up with him. ‘When my then-French-girlfriend invited me to stay with her I jumped at the opportunity.’

It soon becomes apparent that not even Paris’s beating heart could revive Edward’s fading relationship with Alice. The fickle hand of fate strangles their love when she accepts a job offer back in London. Rather than returning to England with Alice, Chisholm decides to switch off the life support to which their relationship was clinging and declares his intention to stay in the city that had captured his heart.

The scene is now set, and the man with wanderlust born in his soul will soon go from dreamer to Down and Out in Paris.

When you initially arrived in Paris, what were your initial hopes and expectations? Did you have any idea of a long-term plan?

I’d obviously romanticised it, picturing myself as some kind of contemporary flânneur who would wander between cafés penning the next great novel. It was a little about giving myself a proper education too, as I’d graduated from university and in almost two years failed to find a decent job.

I wanted to right some wrongs and get some real skills – teach myself another language (which I’d failed to do at school), read and read and read, and then write and write and write. And hopefully, get better. I had no long-term plan in mind, but I knew as soon as I’d arrived, that I was home, and that, wherever I ended up, I wouldn’t be going back to the UK again. Twelve years later I’m still abroad.

Despite doing random cash-in-hand jobs in Paris, there was always something exciting about it. Everything was novel: the sound of the sirens, the taste of the tap water. Also, Paris is so beautiful, so full of history, that it’s a pleasure to be there. It was also easier to be poor there, staples such as bread, coffee, and the metro are a fraction of the price compared with say London. Also, if I moved back to London I would have been couch surfing again and jobless, so it was a no-brainer really (I think I’d exhausted the aforementioned sofas too). I might as well continue the adventure.

During this time you took on quite a few jobs. You worked on a building site and as a museum security guard, as well as a film extra you also flogged soft porn. What are some of your memories from this time? Do you ever think to yourself, I can’t believe I did all that?

When I look back I’m amazed at the tenacity I had. Of course, I was always hoping something that I had written would get published, or perhaps one of the emails I’d written looking for a job would get a response, so in the meantime, I did what I could.

So you find yourself working in a cocktail bar until 3 or 4 am and then you’re starting work as a museum security guard at 7, and it’s deep winter, and after a few hours of sleep, you’re crossing the frozen city as it sleeps. And after a while, you kind of check out of that whole world of careers and investing for your future because you’re living day to day.

The great thing is that it exposed me to so many different people and the city’s different faces. And of course, you end up doing jobs you never quite expected: selling garden gnomes at a market, being paid to tail a guy for a day, flogging the tv rights for soft pornography, filming extra work, anything you can get.

A dysfunctional fraternity bonded together for life

I’m becoming incredibly aware that I have long since finished my coffee, and that I am now essentially a guy sitting in a cafe reading a book. Perhaps seduced by the idea of living in Paris I order myself a pastry and another coffee. As I look out the window and see what is now an unrealistic amount of rain falling like shards of glass from the sky, I am reminded that I am indeed still in Scotland.

It could be worse though. The situation that Edward finds himself in and presents us with is a slightly more terrifying prospect than mine. As it stands, he is in Paris, with no grasp of the language, navigating his way through its unfamiliar streets, looking for work and a place to live. With time and money running out, it takes bold brass balls and perhaps the courageousness of youth to help him find work as a runner at the ‘Bistrot de la Seine.’

“I’d obviously romanticised it, picturing myself as some kind of contemporary flânneur who would wander between cafés penning the next great novel.“

This is where we are truly invited into the Dark Heart of Paris. A side of the city that many never see or indeed knew existed. The Paris that is so often depicted in cinema and glamorised in Hollywood is nowhere to be seen. Emily in Paris this is not. This is where the City of Light is dim and there exists an underbelly of crime, poverty, prostitution, and social inequality, and where the Louvre Museum is nothing more than a mirage.

This is a world of 14 hours shifts, minimum wage, stale bread, coffee and cigarettes. A world where the stench of blood, sweat and tears cling to your clothes like unwanted hitchhikers. A world that only those who have lived it can truly understand.

Behind the curtain of culinary cuisine there lies a dysfunctional fraternity of waiters bonded together for life through shared experiences. Nobody really knows each other’s past and they all dream of fictional futures, holding them close so it might give them hope.

They love and hate each other in moments of joy and despair. They get high on tips like junkies awaiting their next hit and they spend them as fast as they make them. “Tips are for the ephemeral, the finer pleasures in life,” Chisholm reminds us. They live on a constant kaleidoscopic carousel of confusion, castaway from society and into a world that never stops.

What was it like writing the book? Did it feel like a cathartic experience or was it slightly traumatic thinking back to a lot of the things you went through?

My ambition was to create a written portrait of contemporary Paris, warts and all. One that seemed absent from all contemporary literature on the city, which tends towards the idolised, or is based on the experiences of someone that stayed a few months on their parent’s dime.

I guess I wanted to pick up where Orwell left off, say something quietly political, with that socio-anthropological attention to detail that Zola was great at, whilst trying to capture a bit of the paired-down poetry in the prose style of James Salter.

It was never my intention to put myself in the book, I wanted it to be a documentary, about the waiters, but it soon became apparent that my own arc was important and one that would resonate with other people in their early twenties wondering what the hell to do with their life.

In the book, I’m just called l’Anglais, the English Guy, which is what I was called and helped me keep a bit of distance from the character. It’s only at the end of the book that you see my name when I’d finally worked out who I was perhaps. Hopefully, that allows people to project themselves into his shoes too.

From when you arrived in Paris to when you left, how much do you think you changed as a person?

It’s funny, the fact that I spoke no French (and I mean zero, I couldn’t count to twenty) made people just assume I was incredibly stupid. Here was someone in their twenties who couldn’t communicate the slightest idea. So, after mocking me, they’d just get on with stuff. Which allowed me to observe unhindered.

You become so focused on how people speak and what they’re saying, that as a writer it must have really helped. Same with waiting tables, you’re always privy to snippets of private conversations. I now take great pleasure in writing dialogue, in trying to capture it.

Paris changed me immeasurably – it’s not that I was naïve when I arrived, but you have certain illusions when you’re young, the value of your education for one. And then you get dealt a series of blows which leave you wondering what your worth is. Then little by little, you work it out, you work out who you are, you learn what you don’t know, you grow, and for me, all this happened in Paris.

French legionnaires, drug dealers and guerrilla fighters

“I ignore him and fish the lemon out with my fingers – I suck on it before chucking it in the bin.” With his body and mind on the verge of collapsing, you can feel Chisholm’s exhaustion, and you can hear the clattering of dishes and the barking of orders in violent and provocative outbursts of Parisian rage. You are sucked in and spat out onto the pavements of Paris, with every page taking you further away from the Seine and closer to the Hôtel Du Simplon.

It is at the Hôtel Du Simplon where Chisholm finds himself living, essentially sharing a room with the curious and conspicuous character Stéphane. “The harrowing but slightly amusing thought that I’m living with a serial killer does cross my mind.” Throughout the book, Chisholm writes with this compelling dark humour which is woven into each tale and adventure, between his picture-perfect and poetic prose.

Despite the dire straits in which Chisholm finds himself, he never allows it to defeat him and it never dulls the tone of the book. Instead, he finds the humour in any circumstance, and it is most likely this attitude that kept him sane when insanity could easily have taken over.

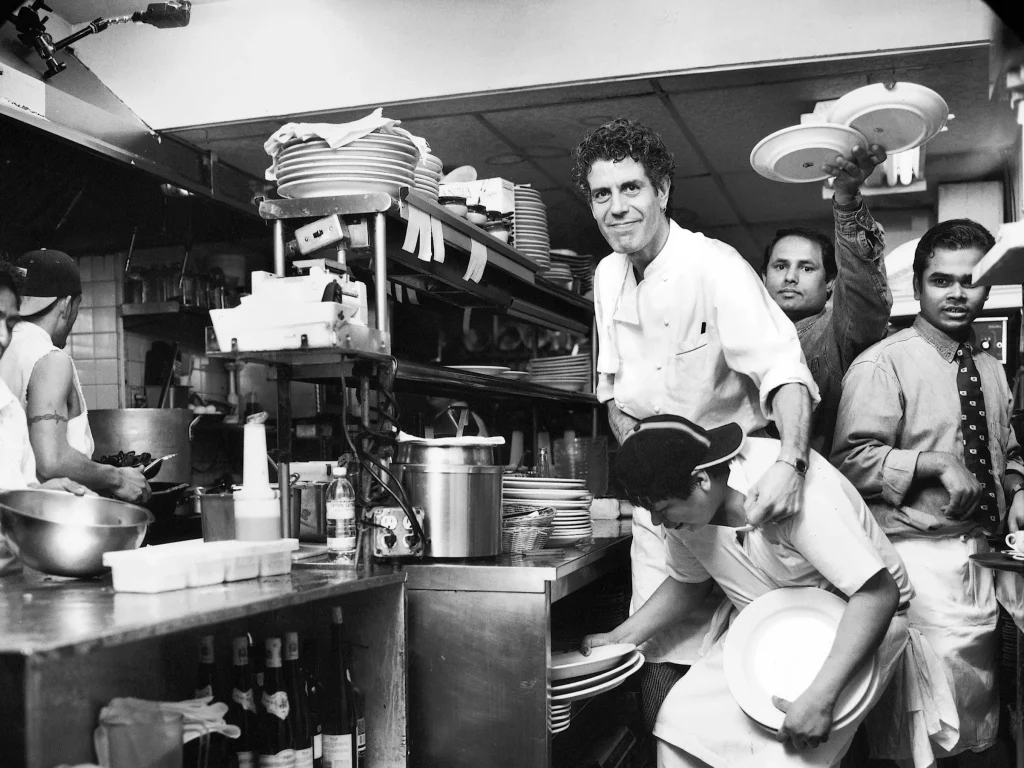

He is not experiencing the Moveable Feast, Hemingway had once described, but instead a never-ending soup kitchen more akin to the world that Orwell wrote about in 1929. There are also comparisons to be made with Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential, which highlighted the brutal nature of an incredibly demanding industry.

“Despite doing random cash-in-hand jobs in Paris, there was always something exciting about it. Everything was novel: the sound of the sirens, the taste of the tap water.”

Chisholm never set out to be a waiter, but in 2011, three years after the financial crash, and two years after graduating from university, that is what he found himself doing. Arriving in Paris with a single bag of clothes, books and a handful of dreams, which would soon be shattered, he began working alongside a French legionnaire, drug dealers, paperless migrants, an aspiring actor, a Communist agitator, and former guerrilla fighters.

Waiters are as prominent as anything in Paris. They are everywhere we look and at the very beating heart of the city’s culinary culture. But how much do we actually know about them and the lives they lead? They are hiding in plain sight, governed by lawlessness and at the beck and call of their dictators. Whilst we as dinners are blinded by the facade presented to us. Drunk on decor and decorum.

“There is an illusion that in being a waiter you are simply waiting on your dream. We socialised at dive bars that served cheap drinks in exchange for the dirty notes that bulged in our wallets. Sleep was snatched on the edge of the city, in thin-walled hovels with shared toilets, scheming landlords, and bedbugs.”

It is this cruel existence that Chisholm articulates so well and he gives meaning to the lives of those we are often ignorant to. “I felt duty-bound to write this book. To give a voice to an invisible workforce. To tell it how it is. So yes, the setting is Parisian, and the language French, but these stories are much more universal; they’re being played out right now in London, Paris, New York, Berlin, Madrid, Rome and beyond.”

Was it always a dream to be a writer and who if anybody influenced your writing?

I didn’t grow up in a house full of books, though as a child I read all the Fleming Bond books and other adventure books. So the profession of “writer” was incredibly vague to me (indeed, it still is). “I didn’t always want to be a writer, no. In fact, as a teenager, I wanted to be a musician. Indeed, I spent a year living in a squat in London trying to make that happen (perhaps a subject for another book). It didn’t, and in a sense, it’s what made me a writer. That I failed as a musician.

However, I remember so clearly aged sixteen picking up Down and Out in Paris and London off a bookshelf at a girlfriend’s parent’s house. I chose it because it was short and then sat down in the garden and read it in one go. Boom, suddenly my mind was opened and the seed planted of Paris perhaps. After that, I was sucked into reading, and a little later writing. I’d always enjoyed expressing myself through writing, but I didn’t realise you could make a living from it (well, just).

As for writers that influenced me, there are many, I’d probably spent most of my twenties trying to ape them at one point or another. We all go through a Hemingway stage, Fitzgerald, etc. Then you’re into Zola, Nabakov, Lecarré. Each one teaches you something (after showing you something you’ll never be able to recreate). I love James Salter, Patricia Highsmith, Albert Camus, the list is endless.

all of France can be found in Paris

It is with deep regret that I find myself running at what feels like a great speed through the streets of Edinburgh. In reality, I’m probably going at a slightly slower and pathetic pace. I have severely misjudged my timings, and I’m looking at the grim reality of missing my train. How could I let this happen? I curse myself as I focus on not having a heart attack.

The wind, rain and cold are no longer an issue. The palpitations I’m experiencing, are now my biggest concern. Am I this unfit? It would certainly seem so. The train station is in sight as I think of Edward and how the dark heart of the city he holds hands with each day, is not just dark, but at times almost apocalyptic, from the late-night metro to the bedbugs he shares his room with and the rats crawling in the shadows of restaurants.

The train is there, sitting and waiting impatiently, preparing itself to leave. I ask myself at what age does one stop running for trains, and simply accept his fate? This can’t be dignified in any sort of way. I see the doors begin to close, I will make this, I will make this, I repeat to myself like some sort of demented mantra. I make it.

I hurtle through the doors, breathing in such a way that leads me to believe I may have some kind of lung condition that is in need of medical attention. I make my way to my seat, ignoring each lingering stare and rejoice in the fact nobody is sitting next to me. I catch my reflection in the window. It is a disturbing sight.

I temporarily ignore my wheezing and pick up where I left off. Edward has integrated himself into life at ‘Bistrot de la Seine’ as a runner, and he has gained the respect of other waiters, and in-between speaking bastardised French and swearing at each other in Italian, Portuguese, Tamil, and Arabic, there is a clear and genuine fondness for those he works with.

In Lucien, he finds a friend who confides in him a dream to become an actor, and they spend nights drinking, smoking and talking about French cinema to wash away the nightmare of a restaurant that haunts them in their sleep. Then there is the charming Scillian, Salvatore the Bear, the kind-hearted soul of De Souza and the enigmatic Piotr. It is this cocktail of characters that blends together to give the perfect recipe amongst all the mayhem and madness.

At times, Chrishom almost thrives on each obstacle that is thrown his way, finding answers to the absurd at each turn. Whether this is navigating the bureaucracy of working and living in France and its maddening labyrinth of loopholes to find a flat or simply seeking out the toilets of a nearby hotel for ten minutes of sleep on a rare break.

He is amid an all-consuming lifestyle which almost becomes addictive and he is witness to an underworld of in-house politics, drugs, fighting and stealing. As time goes by, he begins to sense that he needs to get off this merry-go-round of madness.

By delving into the heart of this restaurant, Chisholm learns not just about himself but others and the society of an often complicated country. As Chisholm explains in his book. “It’s a portrait of contemporary Paris, and by extension France. Slice a Parisian bistro in half and you will be presented with a startingly accurate cross-section of contemporary French society. A multilingual, multi-ethnic, complicated and highly nuanced picture. With the rich and White up top, the poor and Black down below and everyone else – including you – in between. Paris may not be France, but all of France can be found in Paris.”

Life now sees Chisholm living as a writer in Lausanne, Switzerland, and although the days of stale bread, coffee and cigarettes are behind him, you can bet not a day goes by when he doesn’t think of them

How is life in Lausanne treating you? Do you ever miss the hustle and bustle and hectic nature of your previous life? And lastly, ‘A Waiter in Paris’ film or tv series… It’s surely going to happen, isn’t it?

Indeed it is – the book was optioned by Jason Solomons and I have actually just finished the first draft of the screenplay. Indeed we were down at the Cannes Film Festival talking with directors and actors and it’s full steam ahead. You should be seeing some announcements in the press shortly. Watch this space!

Lausanne isn’t Paris, but it is lovely. After just over seven years in Paris, I was ready for a change and at that time I’d become a little obsessed with mountain climbing and cycling. Switzerland offered me the quiet that allowed me to write my book and then a landscape to fulfil my fantasies of being a young George Mallory or Walter Bonatti.

The other great thing about Switzerland (apart from Swimming in the lake every day!) is that I’m only a train ride away from Milano, Paris, etc. For someone who loves Europe, its history, its people and cultures, being in the centre of it all is pretty great.

WHEN YOU’RE IN PARIS THERE IS NOWHERE ELSE.

I finish the last pages of the book as I arrive at London Kings Cross. I walk onto the streets of London, it’s dark, and although it’s late, there is still a hive of activity around each corner. I think back to what it must have been like for Edward to leave behind family and friends all those years ago, embracing the excitement of the unknown. It reminds me that from time to time we all need to throw caution to the wind and adventure often.

Edward Chisholm’s novel isn’t just the story of the people who live and work on the other side of the door marked PRIVE. It is also a love story and an ode to Paris. It may not be the Paris we all know, but for Chisholm, it is a Paris that he fell for.

“Even when you are exhausted, broke and hungry, there’s still an indefinable magic about it. When you are in Paris you couldn’t care less about anywhere else, your world shrinks, and it’s the centre of the universe. There is nowhere else.”

With thanks to the gentleman that is Edward Chisholm. Click here for more information and to keep up to date with Edward’s latest adventures.