All words and images by Guirec Munier

“A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.”

Inside the World of FC St. Pauli

Sankt Pauli. The mere mention of the name evokes a world of its own, stirring strong and often opposing emotions. FC St. Pauli is a neighbourhood club — but not just any neighbourhood. It belongs to the alternative district of Hamburg, Germany’s second-largest city and Europe’s third-busiest port.

This is a district bisected by the Reeperbahn and its surrounding streets, where strip clubs, sex shops, and brothels form the heart of Hamburg’s red-light district. A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.

That spirit would come to define FC St. Pauli itself.

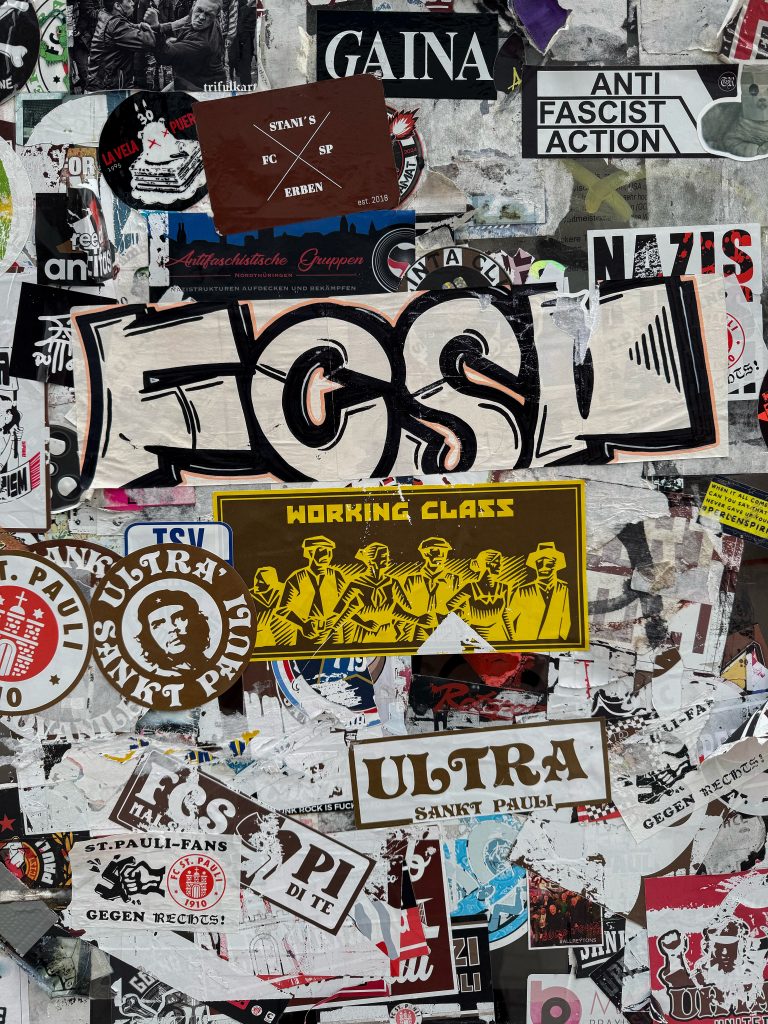

Founded in 1910, the Braun und Weiß club underwent a dramatic transformation in the mid-1980s. Until then largely apolitical, the club took a sharp turn as squatters, punks, and other outsiders found refuge on the right bank of the Elbe. These marginalised groups soon formed the core of the fan base, particularly throughout the 1990s, standing as an island of resistance in a German football landscape plagued by neo-Nazi hooliganism.

Championing anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-sexist values — alongside vocal support for refugees and LGBT+ rights — FC St. Pauli became an emblem of the left. A football club like no other.

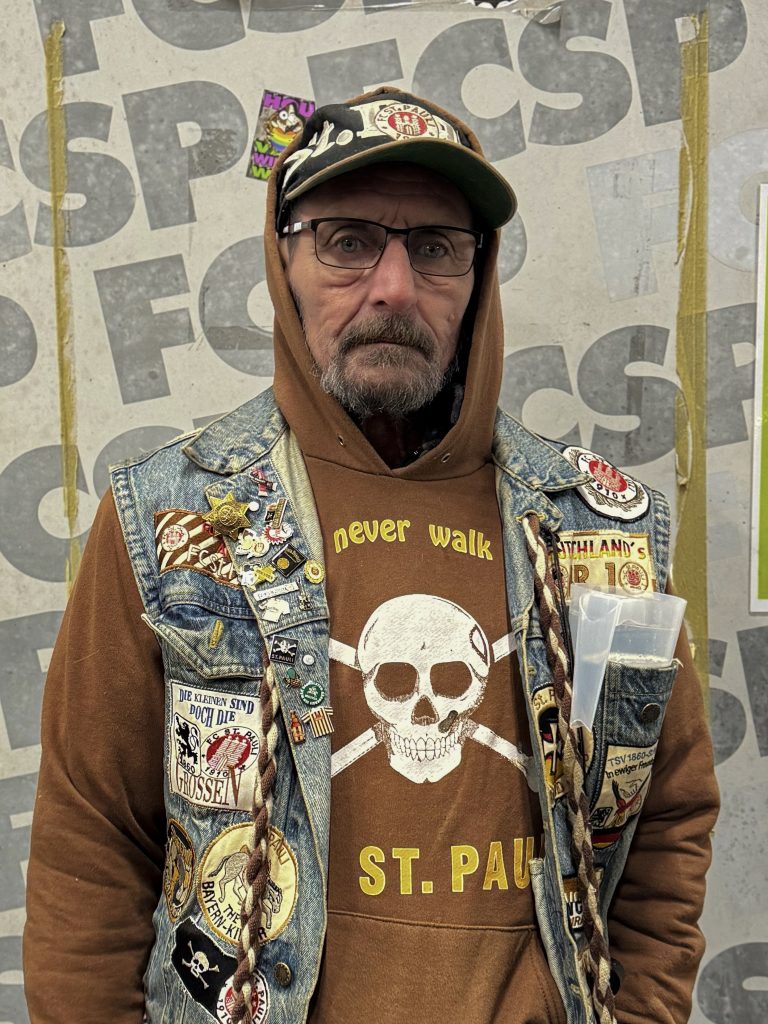

Whatever one might think, football is undeniably political. And what better symbol to represent resistance than a pirate flag? Thus, the Jolly Roger was adopted at the initiative of supporters. Few could have imagined at the time that this gesture would become such a powerful and profitable symbol. So much so that FC St. Pauli supporters are now the only fans in Germany who often don’t wear their club’s official colours.

This fusion of alternative culture and sharp branding has allowed the club to grow far beyond Hamburg and German borders. Today, FC St. Pauli is among the four German clubs generating the highest revenue from merchandise sales, alongside Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund, and Schalke 04.

This commercial success appears to contradict the club’s values — yet how else can they compete without the financial rewards enjoyed by Europe’s elite? Especially when they remain the only fan-owned club playing in one of the top five European leagues.

In a further expression of this model, the club recently sold the Millerntor-Stadion in the form of shares to more than 21,000 supporters. The stadium is now leased back to the club by its fans.

Before every home match, die-hard supporters gather in a convivial space beneath the Gegengerade — the stand holding more than 10,000 standing spectators. Here, alternative subcultures, anarchists, and activists of all kinds mix freely. In the Südtribüne, each game becomes an opportunity to raise awareness or promote a humanitarian cause. At the Millerntor, there is no expectation that you leave your brain at the turnstiles.

Yet divisions have emerged in recent times. Since the war in Gaza, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict has exposed deep fractures within the European left. In Germany, a traditionally pro-Israel stance — shaped by historical guilt linked to Nazism and the Holocaust — increasingly clashes with positions held by left-wing movements elsewhere in Europe, many of which express stronger support for the Palestinian cause.

These tensions are visible within the FC St. Pauli community itself, particularly between local supporters and international fan clubs. Several overseas fan groups have voted to dissolve, and the historic friendship between Ultra’ St. Pauli and the Green Brigade did not survive the fallout.

The German left remains trapped in a German-centric reading of Israeli policy — a stance that continues to divide.

Gegen Rechts. Everywhere.

All words and images by Guirec Munier