The Atlantic Dispatch Studio

The Atlantic Dispatch Studio is the creative arm of our publication, a full-service content studio built on storytelling, design, and culture.

We collaborate with clubs, brands, and destinations to craft campaigns that connect with audiences through authenticity and creativity. Drawing on our editorial expertise in football, culture, photography, and travel, we develop tailored content that resonates far beyond the surface.

Our work spans:

Content Creation — photography, film, editorial, and design.

Brand Storytelling — campaigns that highlight heritage, identity, and culture.

Creative Strategy — shaping narratives that connect clubs and brands to their communities.

Publishing Projects — from bespoke zines to coffee-table books.

We’ve worked with Fiorentina, Legia Warsaw, Hellas Verona, AS Monaco, Visit Naples, Visit Tromsø, Best Arctic, Marek Hamšík, Stanley Lobotka, and more, producing projects that blend football, place, and culture in innovative ways.

At its core, The Atlantic Dispatch Studio is about creating work with depth and meaning — work that not only promotes but inspires, connects, and lasts.

Studio

Words and Images: Joey Corlett

From Middle of the Road to Champions

Watching on from Europe in May 2025, as Club Atlético Platense finished sixth in Group B of the Apertura season, it wouldn’t have been shocking to miss the news in Argentina — let alone anywhere else in the world.

They ended the group stage with a record of six wins, five draws and five losses — about as middle of the road as you can get — yet into the knockout rounds they went all the same. By finishing lower in the table, they were burdened with the pressure of playing away from home, without the support of their fans in the stands.

Despite that disadvantage, they produced a remarkable run, defeating three of Los Cinco Grandes — Racing Club, River Plate and San Lorenzo — all in their own backyards, to set up a historic opportunity: their first-ever Primera División title.

They headed north to the province of Santiago del Estero for the showpiece final against Huracán. In a nail-biting contest, they snatched a 1–0 victory to become Apertura champions.

A Decade of Transformation

Just ten years earlier, Platense had been battling in the metropolitan third tier of Argentine football and only returned to the top division in 2021.

Seeing them put together such a grand run and celebrate with an open-top bus parade through their barrio felt incredibly heartwarming in this era of predictable winners and expectation-driven modern football.

However, fast forward a few months, and I arrived in Buenos Aires. Their title-winning managerial duo had left the club, and they sat bottom of Group B in the Clausura campaign with just two wins in fifteen games.

With the league phase of the Clausura coming to an end — and hopes of reaching the knockouts long gone — I made it a priority to visit the Estadio Ciudad de Vicente López.

One Last Chance

The fixture list offered one final opportunity: the closing match of their dismal run, with Gimnasia de La Plata visiting. Gimnasia themselves weren’t certain of a knockout place, with five teams separated by just three points.

Linking up with Amos Murphy, we hopped into a taxi and headed north. Platense’s home ground is located in the neighbourhood of Florida, right on the northern border where the capital ends and the greater Buenos Aires province begins. Situated alongside one of the main motorways out of the city, we arrived quickly.

A Quieter Corner of Buenos Aires

It was immediately noticeable that this was a quieter, more residential part of town.

Wandering towards the ground, there was a calm atmosphere as we searched for refreshments. We stumbled upon a large group of fans preparing for the evening — trumpets in hand, drums resting at their feet. They were curious about where we were from, made sure we were okay getting tickets and warmly welcomed us. A brief but lovely encounter.

We grabbed refreshments from a corner shop called The Martini’s, draped in brown and white flags. With a busy grill out front and fans snacking on choripán, it did the job perfectly for us. Two cans of Schneider before kick-off.

Welcome to the Home of the Champions

Following the waves of fans over the bridge, we could hear the barra brava already in position. The beautiful musical noise spilled back out of the stadium — the perfect appetiser.

We collected our tickets from a classic little window in the wall, handing over pesos for two paper stubs slid back to us. A small ritual you don’t experience much anymore.

Passing through police and ID checks, the man tearing tickets smiled:

“Where are you guys from?”

When we answered, he ripped the tops of our tickets and simply said:

“Welcome.”

Two gringos were welcome in Platense.

Underneath the popular terrace, we looked out over the green turf. The advertising boards and scoreboard both displayed the message:

“Bienvenidos a la Casa del Campeón.”

(Welcome to the Home of the Champions.)

After a few rounds of chants, we tuned in more closely to the barra brava.

“Are they singing about calamari?”

Yes. Yes, they were.

El Calamar

Platense picked up their nickname back in 1908. Their pitch at the time was close to a river and prone to flooding. Uruguayan journalist Antonio Palacio Zino wrote that the team played its best matches on muddy fields:

“Are they going to play against Platense? In the rain and mud? Then we already know who will win! Platense, in the mud, are like squid in their ink!”

And so, they became El Calamar.

Sunset and Defeat

Despite relentless effort on the terraces — one fan in front of us spent the entire match perched atop the crush barrier, seemingly with calf muscles of steel — the match itself didn’t live up to its side of the bargain.

Both sides struggled for control, but Gimnasia capitalised on Platense’s mistakes. The home goalkeeper failed to claim a simple cross, and Manuel Panaro nodded home after just 20 minutes, setting the tone.

We were treated to one of the best sunsets of my month in the Argentine capital — a stunning backdrop in stark contrast to the lack of quality on the pitch.

The visitors added two more without reply.

As the third went in, right in front of us, one Platense fan turned, wincing, head in his hands:

“This team is horrible.”

Yet when the final whistle blew, contradictions defined the night. That same fan was singing his team off as:

“¡Campeón!”

From the Neighbourhood to the Continent

We watched as banners were taken down — perhaps for the last time as reigning champions — before heading out to finish the night with cervezas and milanesas in a local spot. The perfect way to round off a Monday night in Buenos Aires.

Thanks to their Apertura heroics, El Calamar will play Copa Libertadores football, with “Del Barrio al Continente” (From the Neighbourhood to the Continent) currently emblazoned across the stadium.

After a disastrous Clausura campaign, a fascinating South American adventure awaits.

For one final match, Platense were champions — and they took every second of that last opportunity to celebrate it.

If you get the chance, head north and experience this authentic slice of Buenos Aires football.

Words and Images: Joey Corlett

THE ATLANTIC DISPATCH STUDIO

Studio

The Atlantic Dispatch Studio is the creative arm of our publication — a full-service content studio built on storytelling, design, and culture.

The Buenos Aires Dispatch: From Calamari to Campeón: A Night with Platense

Words and Images: Joey Corlett From Middle of the Road

Brazil and the Unspoken Language of Football

Words and images: Markus Blumenfeld For Markus Blumenfeld, football is

Fields of Passion: Discovering Brazil’s Várzea Football

All words and images: Gaetano Bastone For Naples-born photographer Gaetano

THE ATLANTIC DISPATCH STUDIO

Latest

All words and images: Gaetano Bastone

For Naples-born photographer Gaetano Bastone, football has never simply been a game. It is a language, a ritual, and a way of understanding people. Raised on street football and later combining that early passion with photography through his project INT ’O STREET, Bastone has long been drawn to the raw, unfiltered spaces where the sport truly lives.

In this piece, he turns his lens toward Brazil’s Várzea football scene, a vast and deeply rooted grassroots movement played far from the glamour of elite stadiums. What he discovers is not just competition, but community: Sunday gatherings where entire neighbourhoods come together, where children improvise with makeshift balls, elders grill meat on the sidelines, and organised supporters create an atmosphere as electric as any professional arena.

Through his experience at Campo do X do Morro and his immersion in Brazilian football culture, Bastone reflects on warmth, belonging, and a version of the game untouched by commercial pressures. His story is not just about Várzea football; it is about the enduring soul of football itself, and why, in Brazil, the sport feels less like entertainment and more like life.

I’ve loved street football since I was a child. At 18, I started managing futsal tournaments in my city. I then decided to combine this passion with photography, and the project INT ‘O STREET was born. In the first chapter, I documented the Scugnizzo Cup, the most famous street tournament in my city.

When I arrived in Brazil, I had only one idea in mind: to document Brazilian street football. Várzea football is a huge movement in Brazil — professionally organised tournaments where the protagonists aren’t famous players, but ordinary people with one shared passion: football. Sunday is a day of great celebration. On the sidelines, you can find old men grilling meat, children playing with a can or anything that resembles a ball, and organised supporters cheering on their team. It’s a unique spectacle for football lovers.

It was a truly unique experience. When I arrived at Campo do X do Morro, my first approach was timid. I was there with my close friend, photographer Rafael Veiga (@rveiga_), who explained to the organisers that I was a photographer from Italy. From that moment on, I received a star-studded welcome: direct access to the sidelines, a free official tournament jersey, and interviews. What I love most about Brazilians is their emotional warmth. I immediately felt at home.

If you love football and are in Brazil, you cannot miss the opportunity to attend a Várzea football match. It’s the best way to experience the purest side of the game, free from political or financial interests. Seniors, adults, and children all come together to enjoy a Sunday of football and fellowship. It’s a unique experience that can only truly be had in Brazil.

There’s no real comparison when it comes to football culture in Brazil. Football is everything there, and it’s experienced with immense passion. I used to believe that my city was among the most passionate in terms of football, but after visiting stadiums in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, my perspective completely changed. In Brazil, they sing before, during, and after the game — it’s a constant celebration to the rhythm of samba. People wear the colours of their favourite team throughout the week, not just on matchday. And there is always respect; if you wear a different jersey to mine, you are still my brother. Brazil is different. I’ve missed it since the day I returned home.

All words and images: Gaetano Bastone

All images by Dana Maria Pop-Oprisan

“Football culture in Romania is deeply emotional and built on loyalty.”

For photographer Dana Maria Pop-Oprisan, Universitatea Cluj is not a club that can be measured in silverware.

“U Cluj is special because it has never been defined by trophies or results,” she says.

In more than a century of history, the club has won only one major trophy — the Romanian Cup in 1965. But, as Dana makes clear, that statistic has never defined what U truly represents.

“U is about people who have stood by the team regardless of the times,” she explains. “About the pride of belonging to a community that never gives up.”

For her, the connection is deeply personal.

“For me, U Cluj means family, joy, emotion, and identity, something truly UNIQUE,” Dana says. “These are not things that can be explained in words; they are felt deeply.”

Love at First Sight

Dana’s relationship with the club began instantly.

“I can say it was love at first sight.”

She remembers her first match vividly — not because of the scoreline, but because of the supporters.

“From my very first match the supporters impressed me with their passion, unity, and songs even though the team was playing away from Cluj,” she says.

At that time, the new stadium was still under construction. U Cluj were not even playing in their own city, yet the atmosphere travelled with them.

Since 2010, Dana has remained faithful to these colours, travelling across the country to support the team. The commitment became part of her life — documenting matches, following the club wherever it played, and embedding herself within the community she describes as family.

A European Return After 53 Years

This season brought a historic moment.

“I was also able to experience a European away match as U Cluj returned to continental competition in the second qualifying round of the Conference League,” Dana says, “where U returned after a 53-year absence.”

For a club whose identity has been built more on loyalty than laurels, the return to Europe carried emotional weight. It was not simply about qualification. It was about history reconnecting with the present.

Cluj Arena: Living Football

Today, Dana describes the experience at Cluj Arena in powerful terms.

“The experience at Cluj Arena is intense and emotional,” she says.

“The atmosphere created by the supporters, the chants, the colours, and the energy in the stands turns every match into a special moment.”

What stands out most, however, is the sense of belonging.

“Here, you are not just a spectator but part of the U family that lives football with passion and pride.”

Romania, Cluj and Identity

Dana places U Cluj within a broader cultural landscape.

“Romania is a country of beautiful contrasts with spectacular nature, a rich history, and welcoming people,” she says.

Cluj itself reflects that balance.

“Cluj perfectly represents this combination: a vibrant city with youthful energy, culture, and tradition. It is a place where the past and the present meet naturally.”

That same emotional depth is evident in Romanian football culture.

“Football culture in Romania is deeply emotional and built on loyalty,” Dana explains. “Supporters live football with passion and attachment.”

For many, she adds, clubs represent identity and tradition.

“Even in difficult moments, the bond between the team and its supporters remains strong.”

Something That Is Felt

U Cluj’s history may include only one major trophy. But for Dana Maria Pop-Oprisan, that has never been the point.

The club is not defined by results.

It is defined by people.

By standing by the team regardless of the times.

By the pride of belonging to a community that never gives up.

By family, joy, emotion, and identity.

By something that cannot be explained in words — only felt deeply.

Words and Images: Joey Corlett

Before the Final: A Nervous Send-Off

Across two home games in Lanús, I was lucky enough to witness both the pensive before and the jubilant after, as their barrio club collected its second Copa Sudamericana following a penalty shootout victory over Atlético Mineiro.

Sadly, I couldn’t make the long round trip to Paraguay for the final itself, but from a nervous send-off to an ecstatic return, it was fascinating to observe a rollercoaster three weeks for El Granate up close and personal.

As the birthplace of Diego Maradona — Argentina’s modern patron saint of football — Lanús had long intrigued me while planning my groundhopping itinerary around Buenos Aires. The week before I arrived in Argentina, Lanús had overcome Universidad de Chile 3–2 in the semi-final to book their place in South America’s equivalent of the Europa League showpiece.

On the eve of my second weekend, I noticed Lanús were hosting Atlético Tucumán in their final regular league game of the 2025 Clausura. The home side sat comfortably in the table, having already qualified for the knockout playoff stage, meaning most attention was firmly fixed on the upcoming continental final.

Journey South: Into Granate Territory

Thanks to Jamie and Eduardo, I managed to secure a ticket and set off via the 74a bondi from the microcentro of Buenos Aires, heading south. Lanús lies just outside the capital and forms part of the wider Buenos Aires province.

Home to more than 450,000 people, Lanús is historically tied to industry — chemical, textile, paper, leather and rubber goods all manufactured locally. In researching the area, I discovered that one of Argentina’s most celebrated rock nacional bands, Babasónicos, was formed there, too.

After a 45-minute ride, the grand European-style architecture of Buenos Aires gave way to more modest, residential surroundings. Dropped off a few blocks from the stadium, it was a simple walk into the neighbourhood.

Previa: Meat, Beer and Confusion

I’d arranged to meet some fellow English groundhoppers who had tucked themselves into a local establishment, grills blazing out front with various cuts of meat sizzling away. Everything you could want from an Argentine matchday was on offer: empanadas, choripán, bottles of beer served almost before you’d finished asking.

Somewhere between Spanish and English, we spoke with local fans — several pleasantly baffled as to how we’d ended up in this corner of town. Every one of them was welcoming, proud, and buzzing ahead of the final. We were even offered a seat on one of the many coaches making the pilgrimage across the continent to Paraguay. Sadly, the 26-hour round trip didn’t fit my schedule — but the gesture alone said everything.

Under the Cabecera Norte

Cutting through ticket and ID checkpoints lined with riot police, we approached a stadium whose walls were covered in murals of past heroes and the ever-present Lanús crest.

As we entered under the Cabecera Norte, the noise was staggering. Even outside, it had been ear-splitting. Inside, the barra brava were already in full flow — trumpets blaring, drums pounding, flags and arms moving in hypnotic rhythm.

With the stadium barely 60% full, the volume was astonishing — perhaps many were already travelling north for the final. Atlético Tucumán refused to simply make up the numbers, fighting back to level at 1–1 before half-time. When Lanús saw a second-half goal ruled out by VAR, a murmur of uncertainty crept through the stands.

Fortunately, clinical finishing restored calm. A 3–1 victory sent head coach Mauricio Pellegrino and his players down the tunnel to the popular stand’s applause — as prepared as they could be.

Sunday in Buenos Aires: A City Listening

A week exploring the capital passed before the final arrived.

While Lanús battled for continental glory, I found myself en route to another game in Buenos Aires. Walking through Chacarita, every kiosk with a spare television or radio was tuned into the final. On social media, many had suggested a Lanús victory would reflect well on Argentine football. You could feel that sentiment everywhere.

On the bus, commentary blared from the driver’s radio. Passengers clutched phones streaming the action. We ducked into a bar near our destination to catch the closing stages of extra time as the game drifted towards penalties.

With both opening penalties saved, tension intensified. Lanús goalkeeper Nahuel Losada thought he had sealed hero status by saving Mineiro’s fourth spot kick — only for Lautaro Acosta to blaze over and surrender the advantage.

Into sudden death. Seventh round.

Franco Watson converts.

Vitor Hugo steps up for Atlético Mineiro and scuffs a weak effort to Losada’s right. The keeper gathers easily.

He is the hero after all.

Lanús are continental champions once again.

The Homecoming

Four days later, Lanús hosted Tigre in the Clausura playoffs. I had to see the return.

Eduardo kindly sorted another ticket — this time with a proper Argentine previa included. The same 74a bus carried me south, but this journey felt different. The streets buzzed. Fans in granate shirts filled bars and kiosks. Plaza Sarmiento overflowed with parillas, coolers of Fernet and beer, and fireworks crackling overhead.

Among Eduardo’s friends — some freshly returned from Asunción — pride radiated. We shared Fernet and cola, discussing Argentine and European football, Maradona’s legacy, and Lanús history. The hospitality felt effortless, natural. Football as a universal language.

Smoke, Fire and Farewell

Entering the stadium again, every face was smiling. The popular was packed, bodies pressed shoulder to shoulder.

Fireworks erupted. The barra sang songs of gratitude. Smoke drifted across the pitch as players emerged. Fans scaled fences and poles. One supporter stood high above, shirt twirling overhead.

After layers of celebration, a football match did begin. Tigre, realistic about their task, sat deep. Lanús dominated early but fell behind to a scrappy corner. VAR again denied the hosts an equaliser. Fatigue from 120 minutes in the final was evident.

Tigre progressed. But no one truly cared.

The Copa Sudamericana trophy was paraded around the pitch. Fans climbed for a glimpse. Speeches followed — most notably an emotional farewell to Lautaro Acosta, who bowed out after 429 appearances, the most in club history. Fittingly, his teammates ensured his legacy would not be defined by that missed penalty.

After nearly four hours of chanting and celebration, we left — gratefully accepting a lift back to Buenos Aires, detouring past the hospital where Maradona was born.

A Barrio Club on Tour Again

Seeing the joy on Eduardo and his friends’ faces was a privilege. To witness a historic moment for a barrio club at such close quarters felt special.

With victory comes qualification for the Copa Libertadores and a Recopa Sudamericana showdown with Flamengo. More journeys lie ahead. More away days.

Lanús are going on tour again.

And if you’re lucky enough to be there, you’ll understand why that matters.

Words and Images: Joey Corlett

Football clubs are not built overnight. They are shaped slowly, by players, coaches, supporters, and moments that linger long after the final whistle. In Zwolle, that story stretches back 115 years.

Founded on June 12, 1910, PEC Zwolle reaches a landmark anniversary this season, and the club is marking the occasion in fitting style. Zwolle Originals is more than a kit launch; it is a celebration of identity, continuity, and the figures who helped shape both the club and the city.

Shot with a selection of true club originals — including Jaap Stam, Tijjani Reijnders, and Arne Slot — the campaign bridges generations, bringing together eras that define Zwolle’s footballing DNA.

At its heart, Zwolle Originals is about recognition. Recognition of the players and coaches who left a lasting imprint and whose influence is still felt today. From Bram van Polen to Co Adriaanse, from Henk Timmer to Albert van der Haar, the campaign gathers together names that resonate deeply with supporters.

The anniversary celebrations culminate in Zwolle Originals Matchday on Saturday, January 31st — a moment dedicated to reflecting on the club’s rich history and the people who helped build it. These are the figures many supporters grew up watching, learning from, and celebrating; individuals who turned Zwolle from a name on a fixture list into a shared emotional reference point.

To mark the milestone, the club is also releasing a limited-edition Zwolle Originals 115th anniversary shirt. Featuring all of the aforementioned icons, the shirt serves as both a wearable tribute and a piece of living history.

In an era often obsessed with the next signing or the next season, Zwolle Originals pauses to look backwards, not out of nostalgia, but out of respect. It is a reminder that clubs endure because of their people, their stories, and their ability to honour where they come from.

Reimagining clothing as a moving canvas through Acrylic Fusion.

Reimagining clothing as a moving canvas through Acrylic Fusion.

With anticipation building ahead of this summer’s FIFA World Cup, Scottish contemporary artist Craig Black unveils Atlético Fusion — a visionary art project translating his signature Acrylic Fusion technique from canvas to fabric.

The project reimagines what football apparel — and clothing more broadly — can be when art, culture, and storytelling collide. More than a football shirt, Atlético Fusion explores the idea of clothing as a moving canvas, where colour, texture, and energy shift with the body, allowing art to be lived, worn, and experienced in everyday life.

At the heart of the project is Craig Black’s belief that wearable art is a mindset — a way for art to exist beyond walls, embedding itself into identity, culture, and human expression.

A Case Study in Wearable Art

Presented through a conceptual football shirt and fictional club, Atlético Fusion demonstrates what’s possible when original artwork is thoughtfully translated into wearable form.

Acting as a creative proof point, it shows how Acrylic Fusion can retain its depth, movement, and emotional energy when applied to fabric.

The result is a garment designed to exist both on and off the pitch: a cultural object that reflects ambition, imagination, and individuality, and illustrates how art can help tell richer stories through product.

From Canvas to Clothing

The Atlético Fusion shirt originates from a unique, hand-poured Acrylic Fusion artwork. Using Craig’s distinctive process, layers of colour interact organically, creating fluid motion and captivating visual energy.

That original artwork was then meticulously adapted for fabric, ensuring the textures and rhythm of the piece live within the garment as it moves with the wearer. The process highlights how Studio Craig Black specialises in translating art into new formats without losing its soul — whether applied to clothing, objects, packaging, or environments.

Personal Connection & Creative Journey

For Craig, Atlético Fusion is deeply personal — a way of sharing his own story.

Football was his first love and creative outlet. As a child, he expressed emotion through sketching long before discovering painting, eventually pursuing a career as a professional footballer. Experiencing the sport from the inside gave him a deep understanding of its culture, identity, and emotional power.

Those early drawings and lived experiences have since evolved into an international artistic practice spanning global brand collaborations, live performances, and exhibitions. Atlético Fusion brings that journey full circle — uniting Craig’s passion for football with his distinctive Acrylic Fusion technique.

Storytelling Through Wearable Art

Designed to be gender-inclusive, Atlético Fusion challenges traditional boundaries between sport, fashion, and fine art. It demonstrates how wearable art can communicate values, identity, and cultural relevance — offering a new way to express who we are and what we stand for.

At its core, the project reflects a simple belief:

Art lives beyond walls, and football inspires far beyond the pitch.

Both are powerful cultural languages, capable of telling human stories through movement, emotion, and imagination.

Artist Quote

“Atlético Fusion isn’t about a football shirt — it’s about possibility. It shows how my Acrylic Fusion technique can live on the body and become part of someone’s identity. This is wearable art as storytelling, where creativity moves, evolves, and connects with people.”

— Craig Black

A Timely Cultural Moment

Arriving as the world looks toward a FIFA World Cup hosted across the USA, Mexico, and Canada, Atlético Fusion reflects the growing intersection of sport, fashion, and culture on a global stage.

For Craig Black — a former professional footballer and proud Scot — the project also carries personal significance, aligning with Scotland’s return to the World Cup and reinforcing his vision to bring fine art into new environments, expanding its relevance across industries, communities, and cultures.

About Craig Black

Craig Black is an internationally recognised contemporary visual artist known for his signature Acrylic Fusion technique — a hand-poured paint process that creates mesmerising, fluid artworks. He specialises in telling brand stories through his art. His work spans fine art, commercial collaborations, live performances, installations, and experiential design. Craig has collaborated with leading global brands and continues to push the boundaries of how art can live in the world.

Studio Craig Black

Email: hello@craig.black

Website: https://craig.black/

Instagram: @_CraigBlack

LinkedIn: Craig Black

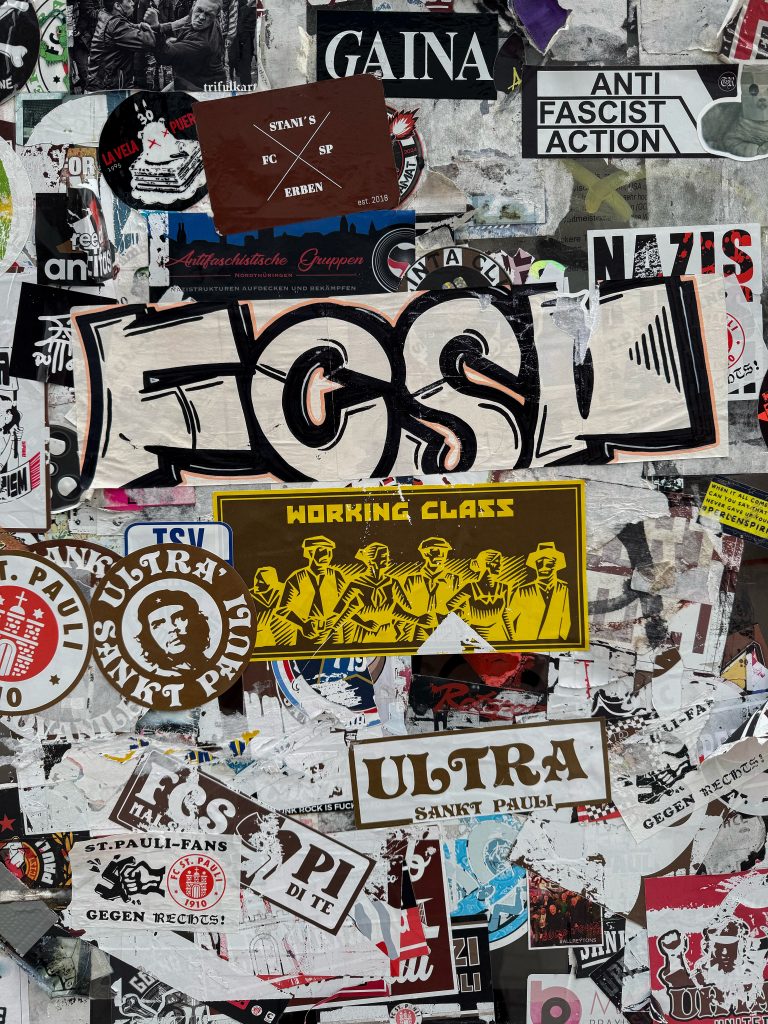

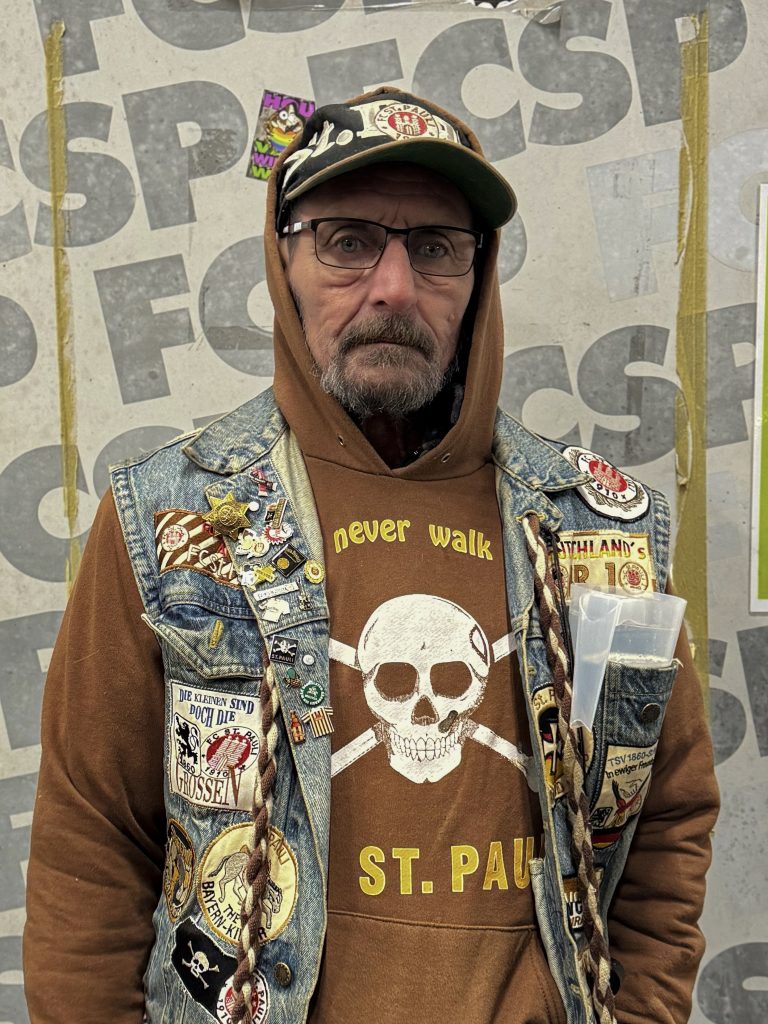

All words and images by Guirec Munier

“A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.”

Inside the World of FC St. Pauli

Sankt Pauli. The mere mention of the name evokes a world of its own, stirring strong and often opposing emotions. FC St. Pauli is a neighbourhood club — but not just any neighbourhood. It belongs to the alternative district of Hamburg, Germany’s second-largest city and Europe’s third-busiest port.

This is a district bisected by the Reeperbahn and its surrounding streets, where strip clubs, sex shops, and brothels form the heart of Hamburg’s red-light district. A place that, despite ongoing gentrification, was forged in adversity — and where defiance remains central to its identity.

That spirit would come to define FC St. Pauli itself.

Founded in 1910, the Braun und Weiß club underwent a dramatic transformation in the mid-1980s. Until then largely apolitical, the club took a sharp turn as squatters, punks, and other outsiders found refuge on the right bank of the Elbe. These marginalised groups soon formed the core of the fan base, particularly throughout the 1990s, standing as an island of resistance in a German football landscape plagued by neo-Nazi hooliganism.

Championing anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-sexist values — alongside vocal support for refugees and LGBT+ rights — FC St. Pauli became an emblem of the left. A football club like no other.

Whatever one might think, football is undeniably political. And what better symbol to represent resistance than a pirate flag? Thus, the Jolly Roger was adopted at the initiative of supporters. Few could have imagined at the time that this gesture would become such a powerful and profitable symbol. So much so that FC St. Pauli supporters are now the only fans in Germany who often don’t wear their club’s official colours.

This fusion of alternative culture and sharp branding has allowed the club to grow far beyond Hamburg and German borders. Today, FC St. Pauli is among the four German clubs generating the highest revenue from merchandise sales, alongside Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund, and Schalke 04.

This commercial success appears to contradict the club’s values — yet how else can they compete without the financial rewards enjoyed by Europe’s elite? Especially when they remain the only fan-owned club playing in one of the top five European leagues.

In a further expression of this model, the club recently sold the Millerntor-Stadion in the form of shares to more than 21,000 supporters. The stadium is now leased back to the club by its fans.

Before every home match, die-hard supporters gather in a convivial space beneath the Gegengerade — the stand holding more than 10,000 standing spectators. Here, alternative subcultures, anarchists, and activists of all kinds mix freely. In the Südtribüne, each game becomes an opportunity to raise awareness or promote a humanitarian cause. At the Millerntor, there is no expectation that you leave your brain at the turnstiles.

Yet divisions have emerged in recent times. Since the war in Gaza, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict has exposed deep fractures within the European left. In Germany, a traditionally pro-Israel stance — shaped by historical guilt linked to Nazism and the Holocaust — increasingly clashes with positions held by left-wing movements elsewhere in Europe, many of which express stronger support for the Palestinian cause.

These tensions are visible within the FC St. Pauli community itself, particularly between local supporters and international fan clubs. Several overseas fan groups have voted to dissolve, and the historic friendship between Ultra’ St. Pauli and the Green Brigade did not survive the fallout.

The German left remains trapped in a German-centric reading of Israeli policy — a stance that continues to divide.

Gegen Rechts. Everywhere.

All words and images by Guirec Munier